Ubiquity in Firefox: Focus on Japanese

One of the eventual goals of the Ubiquity project is to bring some of its functionality and ideas to Firefox proper. To this end, Aza has been exploring some possible options for what that would look like (round 1, round 2). All of his mockups, however, use English examples. I’m going to start exploring what Ubiquity in Firefox might look like in different kinds of languages. Let’s kick this off with my mother tongue, Japanese.1

今後多様な言語に対応したFirefox内のUbiquityを検討していきますが、その中でも今日は日本語をとりあげます。後日日本語で同じ内容を投稿するつもりです。^^ 日本語でのコメントも大歓迎です!

What commands look like in Japanese

Japanese is not only just a verb-final language but it is strongly [[head-final]], meaning it has postpositions instead of prepositions, direct objects come before verbs, and adjectives precede nouns. In terms of how it identifies its arguments, every argument has a postposition/case marker (called a particle in the Japanese literature) which marks its role in the sentence.

A couple common particles we’ll look at in this example include -を (-o) which marks the direct object (accusative case, you might say) and -に (-ni) which acts like English “to” (dative case). The example sentence we’ll look at today is:

| ケーキを | ブレアに | 送って | (ください) |

| kēki-o | burea-ni | okuʔte | kudasai |

| cake.ACC | Blair.DAT</em> | send.IMP | “please” |

| “Please send a cake to Blair.” | |||

(Note: ʔ is a [[glottal stop]]. ACC=accusative, DAT=dative, and IMP=imperative form.)

That final ください is often dropped in very casual speech and, as it adds no new information, we’ll assume today that the user will not enter it. Finally, Japanese doesn’t use spaces in their orthography, so the actual input would be “ケーキをブレアに送って”.

Mockup 1: Particle identification

| One of the major hurdles in working with Japanese is that there are no spaces between the words. The natural first step is to split the sentence up into words, but this is a very difficult problem in [[Natural Language Processing | NLP]] which big name research groups actively work on. |

Fortunately, however, in “Solving the ‘It’ Problem” Aza suggests that, when we encounter ambiguity in our input, we can go ask the user. Great minds think alike, and computer scientist [[Jean E. Sammet]] suggested the same idea way back in 1953:

Using English [or any other natural language] definitely involves the requirement for the computer (or more accurately its programming system) to query the user about any possible ambiguity.

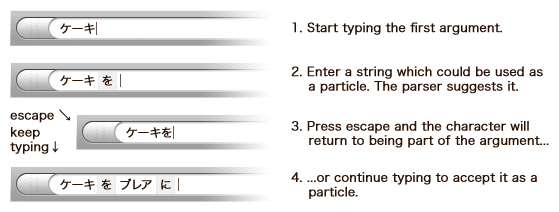

Parsing a sentence into words, in the limited context of Ubiquity, is really about identifying the particles which mark the end of each argument. Here’s a mockup of an application of the Sammet-Raskin Method to this problem:

Pros: This completely takes care of the word-breaking problem, with minimal arbitration from the user. The parser knows exactly what arguments it’s dealing with and the visual feedback means the user won’t be surprised by the parse.

Cons: Most of the particles/postpositions we’d have to deal with are a single character, so they may show up pretty often within words, in which case it would be quite annoying to have to press escape after each one.

An even smarter system, when wanting to mark a character as a particle, would first check to see that the argument (before the particle) is a valid argument type for that particle. If the check fails, it doesn’t have to bother with suggesting that character as a particle. This may cut down on the false positives.

Smart suggestions: what works, what doesn’t

One of the key suggestions in Aza’s mockups include a way to choose the prepositions while entering your arguments, based on the current verb.

For example, here, the translate command accepts a direct object, a to-object, and a from-object, so little to and from markers magically show up on the right side, making the appropriate prepositions (and by extension the appropriate arguments) discoverable. I think this line of thinking is a really good one, at least for English.

In a verb-final language, however, you enter the arguments first and then the verb, making this strategy of suggesting appropriate arguments impossible. Note that in the user-contributed spreadsheet of how languages identify their arguments we see that about a quarter of the languages we looked at are verb-final—that is, with Subject-Object-Verb canonical word order.

Instead of seeing this as a disadvantage, however, let’s see what verb-final order allows us to do.

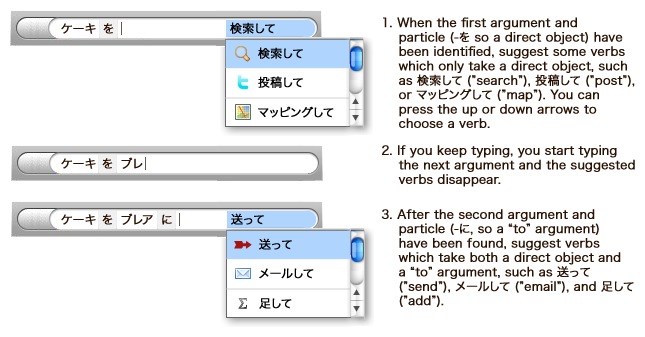

Mockup 2: A different kind of suggestion

Not all verbs allow for every different kind of particle. For example, it doesn’t make sense to have a -に (-ni, “to” or dative) argument for a verb like 検索して (kensaku-shite, “search for”). In English we used this to suggest different types of arguments given a specific verb. In a verb-final language, we could do this backwards.

Pros: This makes verbs highly discoverable, given a certain argument structure. For example, if you enter a few arguments, like a direct object, a “to” argument, and a “from” argument, it’ll suggest verbs that will do something to an object from somewhere to somewhere else. This way, you can easily try out verbs you didn’t even know existed. It’ll only give you verbs appropriate for your arguments, reducing the chance of writing a an infelicitous command.

Cons: Without knowing what kinds of actions are available, it may be difficult to know what kinds of arguments to enter in the first place. If you have a specific verb or service you want to use it may be counterintuitive or downright tricky to start by guessing the right set of arguments.

In addition, from a technical point of view, this requires much of the prediction algorithms in English Ubiquity to run backwards. Ideally, there would be a closed (predetermined) class of particles and a predefined set of noun types. Verbs would not be able to define their own modifiers and noun classes as easily or freely as they can now.

Conclusion

The properties and challenges of Japanese grammar require that we not try to outright copy the English behavior but to think about what really makes sense in that language and that may be an important lesson as we move toward designing a localizable Ubiquity. Please post your questions and criticisms of this design or post your own mockups!

-

Happy International Mother Language Day! ^^ ↩