In Case of Case…

A recently hot topic of discussion in the Ubiquity i18n realm has been how to deal with strongly case-marking languages. As we continue to make steady progress, this is one of remaining open questions which we must decide as a community how to tackle in Parser 2.

Introduction

[[Grammatical case]] is a marking on nouns that express grammatical function. Not all languages exhibit case. In many of the Indo-European languages we hope to bring Ubiquity to, case is realized as a suffix.1

Here’s a classic example of case from [[Latin]]. (Line 2 is the gloss of 1, line 4 of 3.)

canis virum momordit

dog=sg.NOM man=sg.ACC bite=3sg.perfect

vir canem momordit

man=sg.NOM dog=sg.ACC bite=3sg.perfect

Example (1) is “the man bit the dog,” while example (3) is “the dog bit the man.” The only difference, as you see in the gloss, is that the nouns canis and vir are marked with different case endings in the two sentences. By marking the nouns with different cases (here, [[nominative]] and [[accusative]]), their semantic roles in the sentence—which is the the biter and which is the bitee—can be identified unambiguously. (Their positions are also switched in these examples but in reality Latin has a very free word order—the same sentences with other word orders including OSV or VSO are also common.)

At first glance, strongly case-marked languages may look like a godsend for identifying the semantic roles of arguments.2 If we can easily and unambiguously recognize arguments’ cases to put them in their appropriate semantic roles, this could simplify processing as well as make Ubiquity input follow a natural syntax for such languages. Unfortunately, there are some significant challenges which must be overcome in order to make the processing of case-markers worthwhile.

The case against case

There are broadly three different difficulties with dealing with strongly case-marking languages: (1) how to identify case correctly, (2) how to identify the boundaries of the arguments, and (3) what case to use when handing the arguments to the verb’s preview and execution.

Parsing for case

In some languages, it is very easy to recognize different case endings. For example, for Turkish it would be relatively easy to write a regular expression for each of the cases below, even with the [[vowel harmony]] as exhibited in the genitive and accusative cases between i and ü.3

| Case | Ending | köy “village” | Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominative | Ø (none) | köy | village |

| Genitive | -in | köyün | the village’s |

| of the village | |||

| Dative | -e | köye | to the village |

| Accusative | -i | köyü | the village |

| Ablative | -den | köyden | from the village |

| Locative | -de | köyde | in the village |

(Example from [[Turkish language]] on Wikipedia.)

However, in many other languages identifying case affixes can be quite difficult as they vary greatly depending on the root noun, not to mention irregular declensions. For example, in Polish the nominative student becomes the studenta in the accusative which may look like a simple suffix, but the nominative pies (“dog”) becomes psa while stół (“table”) remains unchanged.4 Writing rules for these differing (and sometimes not unambiguous) case-marking paradigms without building in lexical information would be very difficult indeed.

Finding the edges

Recall that the current Ubiquity Parser 2 design identifies arguments by identifying known delimiters (most often some adposition) as a left or right edge of an argument. By not having to run the nountype detection over every substring of the input, we greatly reduce the processing time needed in each parse. This approach, however, relies on our being able to reliably identify some sort of boundary for each of our arguments.

In strongly case-marking languages, the case is realized on the noun itself, but this noun may be buried in the middle of the noun phrase. Even if we could reliably identify the case-marker, it would mark neither the left nor right edge of the argument, making our current parsing strategy worthless. For example, consider the following Arabic example of “the house of the man” in nominative and accusative cases:5

baytu 'r-rajuli

house=NOM of=man

bayta 'r-rajuli

house=ACC of=man

In these cases, we see that the only distinction between (5) (بَيتُ الرَّجُلِِ) and (7) (بَيتِ الرَّجُلِِ) is the case suffix on the head noun, “house,” which sits in the middle of the noun phrase. Even if we could properly identify this case ending, it would mark neither the left nor the right edge of the entire argument.

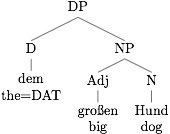

Contrast this with German where, even though arguments have case, the case is realized on the article, not on the noun head itself, so we can essentially deal with these articles as prepositions, using the article as the left edge of the argument.

den großen Hund

the=ACC big dog

dem großen Hund

the=DAT big dog

Believe it or not, things can actually get even worse than just not being able to find an edge of our arguments. The worst-case scenario comes from discontinuous constituents, in languages where case marking on both nouns and modifiers allow for very free word order. Latin is just such a language:6

From M. Tullius Cicero, “Against Catiline,” chapter 1:

quem ad finem sese effrenata iactabit audacia?

what=sg.ACC to extent=ACC self unbridle=perf-past-part.3sg.NOM fling=future.3sg audacity=sg.NOM

“To what extent will (your) unbridled audacity fling itself about?”

In this example we see that effrenata is modifying audacia but the two do not form a unit in the linear order but their relationship can be recovered because both words carry the nominative case marking. While it would be unfair to expect Ubiquity to ever be able to properly parse such arguments, requiring a certain amount of discipline from the user, this is an illustration of how bad things could get if we took the processing of case-markers to the extreme.

The proper case for execution

The final difficulty in processing case-markings in Ubiquity comes from the preview and execution stages of a Ubiquity command’s usage. That is, after we parse the input, we must give the verb the arguments we found so that it can display a meaningful preview or behave correctly when executed. At this point, what case should the noun be when we hand the string of the argument to the verb?

![]() photo credit: Platinatore

photo credit: Platinatore

For example, consider the Latin expression “cave canem!” meaning “beware the dog!”

cave canem!

beware=imperative dog=sg.ACC

Supposing for a moment that we’ve implemented the cavere (“beware”) verb in Ubiquity and properly parsed “cave canem,” should we pass the literal string “canem” in accusative case to the verb, or the nominative string “canis,” or the root “can-“? Which is more appropriate? If “canis” is the more appropriate choice, Ubiquity would then have to be responsible for declining the accusative into a nominative… for all case-marked languages. This is clearly a road we do not want to go down.

Proposal: only support determiners and adpositions

I’ve laid out three reasons why processing strongly case-marked languages in Ubiquity is a non-starter. Fortunately, languages often have multiple different strategies for accomplishing similar communicative tasks. One oft-used strategy for marking different roles of arguments is the use of adpositions (a fancy term for prepositions and postpositions). Unlike case-markers which often are affixes on nouns, prepositions mark the beginning of an argument and postpositions the end, as is used in the current parsing strategy.

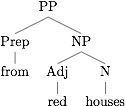

From a formal/theoretical perspective, adpositions sit above the noun phrase proper, while modifiers like adjectives live within the noun phrase. This reflects the fact that, with few exceptions, adpositions mark an edge of the noun phrase, which is crucial to our parsing strategy. (Here, PP is a prepositional phrase and NP is a noun phrase.) Note also that for languages such as German which marks case on determiners (D), the same logic holds.

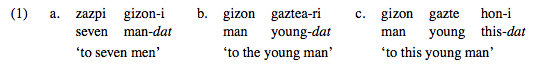

Note also that, as long as the case-marking is phrase-marking (i.e. marking the edge of the noun phrase) rather than just affixing to the head noun, our parsing strategy will work. This means we could possibly in the future write a simple RegExp to split off the Basque dative suffix, as it marks the end of the entire noun phrase. This can be seen in the following data from Tseng (2004), where the suffix -(r)i affixes to the last word in the noun phrase, no matter the type of speech of that last word. (Basque is crazy cool!)

Conclusion

In this blog I’ve outlined some reasons why it would be unreasonable or very difficult to incorporate case-marker processing into our current parser strategy. The case markers themselves are often hard to identify, the case markers do not align at the edge of arguments, and there is the question of what form of the argument should be passed to the verb for preview and/or execution. Luckily many languages allow for adpositions (prepositions and postpositions) as an alternative strategy to case as a means of marking the different grammatical functions of arguments. By limiting Ubiquity parsing to adpositions (and case-marked determiners), I believe we are able to reach a good compromise between each user’s natural language and an easily machine-processable form.

-

Note that when linguists talk about “case,” they could be referring to two different (though related) concepts: case (lowercase) is the observed pattern of affixes on nouns which indicate grammatical function, while Case (uppercase) refers to a theoretical (formal) feature of syntactic objects—certain lexical items “assign Case” or “receive Case” and its mismatches were ruled out in [[Government and binding theory GB]] syntax by the Case Filter. You’ll find GB linguistics papers referring to “case” when discussing Mandarin Chinese, for example, a language that doesn’t have any overt case (lowercase) and you’ll know immediately that this usage is an uppercase Case case. In this blog post I’ll be dealing primarily with the former descriptive notion. -

When I refer to “strongly case-marking languages,” I am referring to languages with a non-trivial inventory of cases (not just nominative, accusative, and genitive) and where a noun phrase’s case is not reflected on [[determiner (class) determiners]]. For example, [[German language German]] is excluded by this definition as case is realized exclusively on articles and there is no need to find and parse the noun head itself to identify its case—more information on German is in the section “finding the edges.” -

In reality Turkish case morphology does get a little more complicated than this with some consonants shifting as well, but it is still possible to identify Turkish case with regular expressions. ↩

-

For those of you who were curious, this difference in Polish is based on the differing genders of each of these words. Data from [[Polish language]] on Wikipedia. ↩

-

Example from [[Iʻrāb]] on Wikipedia. ↩

-

Thank you to Bailey Pickens for help with the Latin data. ↩