A Visual Guide to Community Command Localization

A natural language interface is only “natural” if it’s in your natural language. With this mantra in mind, we’ve been making steady progress on the challenging problem of Ubiquity localization. The first fruit of this research is in the localization of the parser and bundled commands in Ubiquity 0.5. Here today is a visual guide on command localization in Ubiquity and different options we can take in attacking the community command localization problem.

Command localization in Ubiquity 0.5

A few important design decisions have already been made in implementing command localization in Ubiquity 0.5. The first was the choice of the [[gettext]] po (portable object) file format. The po format is a de facto industry standard with many tools built for the format and this design choice hopefully lower the bar for prospective localizers.

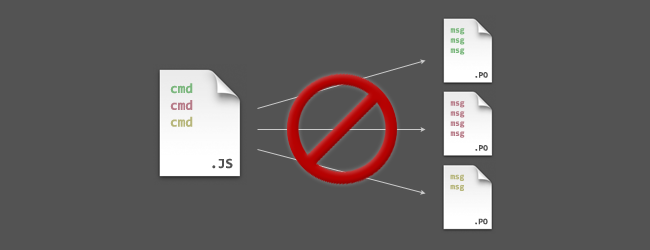

Second, in order to simplify the matching of localizations and commands, we require that each command feed have one localization po file, rather than splitting the localizations of different commands across multiple po files.

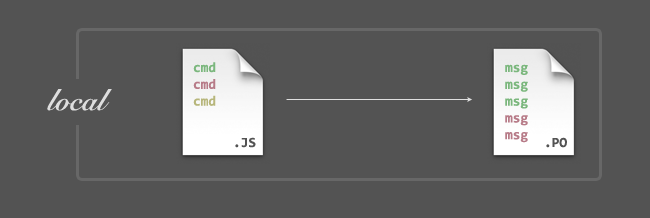

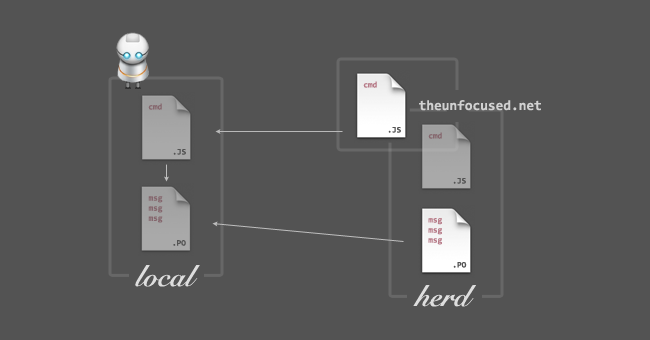

Finding the appropriate localization po file for a JavaScript command feed is very simple with bundled commands as the files are managed in our main repository so we know exactly where to find them. We just take the command feed’s filename sans extension—the feed key—and look for localizations/lang/feed key.po, where lang is the active language code. This gives us a simple one to one relationship between the JavaScript command feed source and the appropriate localization.

Background

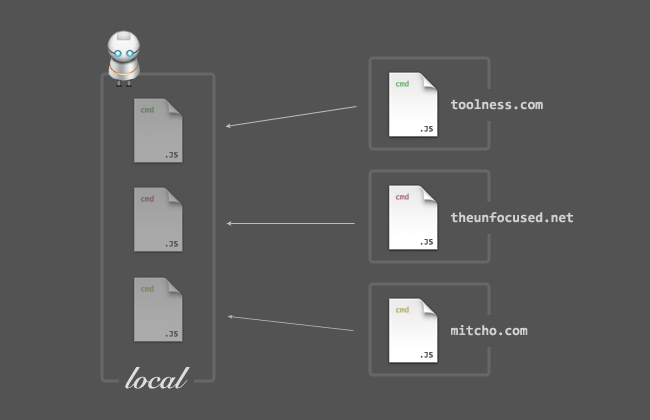

The ability of users to easily write their own Ubiquity commands has always been a huge strength of the Ubiquity platform. Users can also “subscribe” to commands written by other users on other servers. In this case, local copies of those command sources are made.

The herd was developed as a dynamic aggregator of community Ubiquity commands. The herd keeps its own copy of each command source. The herd groups mirrors of command feeds on multiple servers together as well, giving each unique command feed a unique ID.

Localizing distributed resources

This distributed nature of the command feeds is exactly what complicates the localization of community commands. The original sources themselves are distributed, and we also want a community of localizers to be able to localize the commands—i.e., for the localizations to be (in some sense) distributed. Here I will present three options which I believe could be the basis for a winning solution, in order of more distributed to less distributed.

All three of these options have the property that localizations do not need to be “approved” or “managed” by the command author. For example, a possible standard where URL’s of localizations must be in the command feed is not considered. I believe this is a crucial property of any approach we decide on.1

Option 1: a completely distributed option

In this option, localizers simply put the po files on their own servers (or some code snippet site such as github) and the user must then subscribe to those localizations much as they subscribe to commands now.

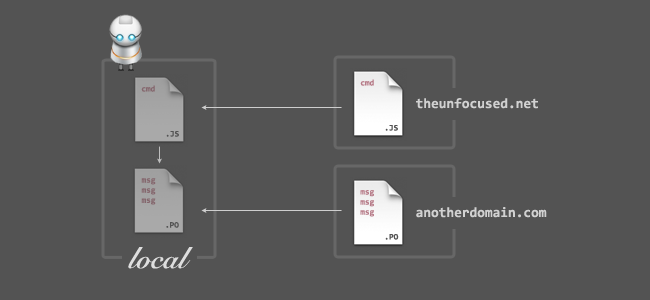

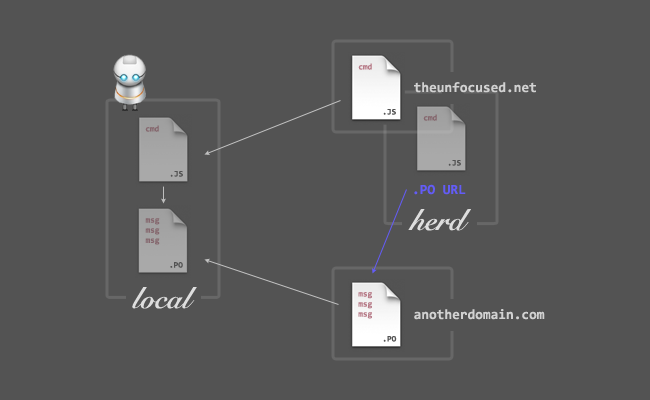

Option 2: registration and discovery through the herd

In this option, localizers put po files up on their own servers and then register that po file’s URL with the herd. The herd keeps track of each command feed’s localizations in different languages.

Option 3: localizations on the herd

In this option, po localizations are uploaded right onto the herd. The herd is the centralized repository of all localizations for each command feed.

Users first

In coming up with a criteria for judging different models of community command localization, I think it is helpful to think of the end-user experience. Right now to subscribe to a new command a user must find the command (perhaps via the herd) and click on the subscribe button, then in most cases confirm that they are aware of the possible dangers and confirm subscription.2 What work is required for a user to subscribe to a new command and get it in their language?

![]()

Under option one, the user would somehow have to find the localization scattered someplace on the internet of their own accord, and then install that localization by themself. In my mind, this is clearly a no go. With options two or three, however, when a user subscribes to a command feed Ubiquity can check with the herd to see whether there are any localizations available. The localizations could be offered to the user or the localization for the currently active language could be automatically installed. There are, on the other hand, disadvantages to requiring a centralized authority, exemplified by the fact that the current iteration of the herd itself has often been down.

Summary and a call for comments

As laid out in this visual guide, I personally have a couple main criteria which I believe we should follow:

- localization independence: Command authors should not have to manage their commands’ localizations. (See footnote 1.)

- friendly discovery and subscription: Users should not have to go out and find localizations by themselves. Localizations should be offered to the user.

With these criteria, I’m pretty sure the only logical conclusion is that we need some level of centralization, pointing to options two and three. If you think of another option which satisfies these criteria, or disagree with the criteria above, I would love to know. In addition, have you encountered similar problems of localizing distributed resources elsewhere? What worked there?

If this problem has been solved before, there is no need to reinvent the wheel. As far as I can tell, however, this could be a particularly hairy problem.

-

This strong view is based on my own experience as a WordPress plugin author and a subsequent conversation with [[Matt Mullenweg]]. The WordPress plugin ecosystem requires that plugin authors orchestrate localizations and bundle them into releases. In the case of my plugin, this requires regular contact with over a dozen localizers.

The case of WordPress plugins is actually much like that of Ubiquity commands… the plugins can be served on any server, distributed, but there is also a central repository, wordpress.org/extend.

Matt and I agreed that if localizers could somehow localize plugins without going through the command author, most of whom produce their plugins by volunteering their time, the localization of plugins could be much more popular. Indeed, some localizers go ahead and publish po files for popular plugins, but those localizations are hard to find as there is no repository for the localizations either. ↩ -

As I’ve written before about Ubiquity’s command subscription, there is much we can improve in this area of Ubiquity’s user experience. ↩