Three ways to argue over arguments

UPDATE: Contribute information on how your language identifies its arguments here.

When we execute a command in Ubiquity, in very simple terms, we’re hoping to do something (a verb) to some arguments (the nouns). Every sentence in every language uses some method to encode which arguments correspond to which roles of the verb. Here are a couple examples:

He sees Mary.

彼が Maryを 見る。 (Kare-ga Mary-o miru.)

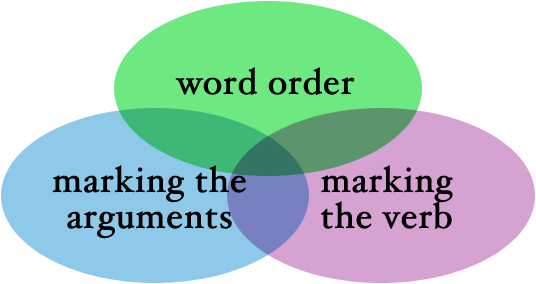

As speakers of English, you can read sentence (1) above and know exactly who is doing the seeing and who is being seen and speakers of Japanese can get the same information from (2). How do different languages code for arguments in different roles? There are, broadly speaking, three different ways:

We’ll take a brief look today at these three different strategies, all of which a localizeable natural language interface will surely encounter.

Word order

In many languages, the position of the arguments relative to one another and to the verb determine the roles which each argument will play. Mandarin Chinese is a good example of such a language:

他 喜欢 Mary (Ta xihuan Mary)

Mary 喜欢 他 (Mary xihuan ta)

Here, sentence (3) says “he likes Mary” while sentence (4) says “Mary likes him”. Simply reversing the positions of “he/him” and “Mary” we’re able to flip the roles that they fill in the sentence: that of the person who does the liking and the person who is being liked. Now take a look at sentence (5) which means “John says ‘hello’ to Mary.”

John 告诉 Mary "你 好" (John gaosu Mary "ni hao")

We note here that, while in English we used a different strategy of marking one argument (we marked the “hello” argument with “to”), Chinese doesn’t mark either of the arguments. There is, however, a clearly defined order to the arguments, which you might encode this way:

say [who you're speaking to] [what you're saying]

If you swap the order of the two objects in this sentence, it becomes ungrammatical. (Note: the asterisk * here means the sentence is ungrammatical.)

* John 告诉 "你 好" Mary (John gaosu "ni hao" Mary)

Here, the word order dictates that “你好” must be “who you’re speaking to” and “Mary” must be “what you’re saying,” but that doesn’t make sense, so the sentence is ungrammatical.

Marking the arguments

Another possible strategy is to mark each argument (or some of the arguments) so that each argument’s role is clear. In many languages this is done with [[case marking]]. Take for example this Ancient Greek sentence with its English gloss on line (6). Here, NOM refers to [[nominative case]] and ACC refers to [[accusative case]].1

ho didaskal-os paideuei to paidi-on (SVO)

the teacher -NOM teaches the boy -ACC

This sentence means “the teacher instructs the boy.” While sentence (5) is in Subject-Verb-Object order, any of the six possible orderings of {subject, verb, object} are also grammatical and mean the same thing:2

ho didaskalos to paidion paideuei (SOV)

paideuei ho didaskalos to paidion (VSO)

paideuei to paidion ho didaskalos (VOS)

to paidion ho didaskalos paideuei (OSV)

to paidion paideuei ho didaskalos (OVS)

| Many languages also use [[adposition | adpositions]] (prepositions and/or postpositions) to further clarify the role of an argument in addition to case (like English does) or in lieu of case marking altogether. The idea is the same, though: you want to clarify the roles of the arguments so you morphologically mark the arguments with their roles. |

Marking the verb

Many languages mark the verb with some information about the argument in a certain role, so that we can properly identify the argument’s roles. This kind of phenomenon is called agreement.

The most common type of verbal agreement is subject agreement, where the verb is marked by a specific form depending on some features of the subject. Anyone who’s taken French 101 will recognize this verb conjugation paradigm:

| subject | être (to be) | |

|---|---|---|

| singular | je (I) | suis |

| tu (you) | es | |

| il/elle (he/she) | est | |

| plural | nous (we) | sommes |

| vous (plural you) | êtes | |

| ils (they) | sont |

With this paradigm, if you hear or see “suis” in a French sentence, you immediately know that “je” (I) must be the subject and if you see “sommes,” “nous” (we) is the subject, etc. [[Standard Average European]] languages tend to exhibit this sort of subject-verb agreement.

Features of the subject position aren’t the only thing that can be marked on the verb, though. Hungarian, for example, has a type of object agreement. Specifically, the verb marks whether the object is definite or not (in linguistics lingo, “the verb agrees with the object’s definiteness feature”).

John lát egy almát.

John sees an apple

John látja az almát.

John sees the apple

Notice that in sentence (12) (glossed in (13)) the verb for “see” is realized as “lát,” while in (14) it’s “látja.” A speaker can use that agreement to see whether the object is definite or not and thus limit the possible object arguments out of all the nouns in the sentence.

All of the above

Most languages do not use only one of these strategies, but a combination of them. English is a very good example. In a sentence like (12) below the main coding of grammatical roles seems to be word order alone. By reversing the word order into (13), we can effectively swap the argument’s roles.

John likes Mary.

Mary likes John.

However, this doesn’t work with pronominal arguments. Swapping the arguments in (14) yields (15) which is ungrammatical due to the case marking on the pronouns.

He likes her.

* Her likes he.

In addition, the verb in English must agree with the subject’s number (singular or plural):

John likes them.

* They likes John.

They like John.

In this way, English exhibits all three strategies: word order, case marking, and agreement, although often only word order is actively used to disambiguate the roles of arguments.

Question: What strategies are used by your language to mark the roles of different arguments?

-

The following example is from Holger Diessel. ↩

-

“Mean the same thing” here means that the teacher is always instructing and the boy is always being instructed. The sentences may differ in when or how they are used depending on which argument is being talked about or what the implications of the utterance are. The formal notion is truth-conditional equivalence. ↩