Solving Another Romantic Problem: Weak Pronouns

Yesterday I blogged on how to deal with portmanteau’ed prepositions in Ubiquity Parser 2, a common problem in various romance languages. Today I’ll propose an approach to another romantic problem.

The problem:

Weak pronouns in [[romance languages]] (as well as some other languages) have a special property where they cliticize to the verb, moving from its regular argument position to a position next to the verb. For example, in French, we have an imperative like (1) with gloss as (2):

Envoyez le lettre à Pierre!

send.IMP the letter to Pierre

If we replace le lettre or à Pierre with a preposition (le, “it”, or lui, “to him”, respectively), those weak pronouns move next to the verb—in particular, (5) exemplifies the change in word order. Replacing both arguments with prepositions creates the stacked clitic form of (7).1

Envoyez-la à Pierre!

send -it to Pierre

Envoyez-lui la lettre!

send -him the letter

Envoyez-le-lui!

send -it-him

The fact that these weak pronouns are attached to the verb and lack separate delimiters mean that we will need a separate mechanism to parse these arguments: indeed, this functionality has been planned in Ubiquity Parser 2 as “step 3”. Here I’ll examine some data and discuss a strategy for the parsing of weak pronouns.

Weak pronouns in Ubiquity

In Ubiquity the only pronoun we currently deal with is the deictic object-role anaphor, like “it,” “this,” etc. in English.2 In addition, as these weak pronoun clitics cannot by definition be embedded within a larger noun phrase, its referent would constitute the entire object argument. As such, it is most logical to place clitic handling before argument structure parsing and simply hand the argument parser the argument string without the clitic.

Marking the clitic

We can classify languages with cliticized weak pronouns into two cases based on their processing considerations: languages that overtly mark the clitic and those which do not.

Languages which delimit the clitic

Some languages such as French (see above) clearly mark the boundary between the verb and the clitic. It will be relatively easy to parse weak pronouns in such languages as we can simply insert a no-width space between the verb and the clitic. A list of clitics can then be designated in the parser (much like anaphora are now) and these weak pronouns can be interpreted as the selection (or “this”-referent).3

Portuguese: (from Cysouw 2003)

Come-o

eat -it

Catalan: (from Toni Hermoso Pulido)

Cerca-ho

search-it

Modern Greek: (from Rivero and Terzi 1995; I know, I know, Greek’s not a romance language, but it has weak pronoun clitics too… it’s all good.)

Modern Greek actually inserts a space between the verb and weak pronouns.

Diavase to

read -it

Languages which do not delimit the clitic

Some languages do not insert any delimiter between the verb and the weak pronoun, essentially entering them as a single word (in the string sense, at least). These cases may be more difficult to parse, especially as there may be sound changes to the verb stem itself.

Italian: (first example from Kayne 1994)

Italian is a case where some verbs actually conjoin with the verb in imperatives, much like their prepositions which I noted yesterday have an elaborate system of portmanteau’ed forms.

Fallo

do-it

Mangialo

eat -it

Spanish: (first example from Rivero and Terzi 1995, second from Toni Hermoso Pulido)

Spanish is the same way:

Léelo

read-it

Búscalo

search-it

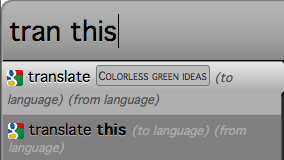

Displaying the suggestion

The current Ubiquity handling of anaphora (aka “magic words”) involves a display of the selection (replacement) text in a stylized way. One problem with clitics may be how to visually present this replacement to the user.

For languages with a delimiter such as French we could simply present the selection as an object right after the verb, without the hyphen.

| input: | traduisez-le (translate-it) |

|---|---|

| suggestion: | traduisez selection |

Things may be more complicated, however, in languages where the clitic is not delimited from the verb, or where the verb form itself has changed due to the attachment of the clitic.

Conclusion

In this blog post I’ve tried to lay out some of the weak pronoun phenomena relevant to Ubiquity with some ideas on how to implement its parsing. I believe parsing weak pronouns should be relatively straightforward in languages with delimiters—for those which do not have delimiters, some creativity may be required in how building regular expressions or rules to detect the clitics and in presenting these suggestions to the user.

Does your language have weak pronoun clitics? What do you think will be the challenges in trying to parse these arguments?

-

Note that the reverse order of “Envoyez-lui-le” is ungrammatical… fortunately we most likely will not have to deal with multiple clitics… see footnote two below. ↩

-

This is not so much an informed decision that we should not do different kinds of anaphors but simply that we haven’t gotten around to implementing it. I personally am not sure, however, whether there is a real need for parsing for anaphors for roles other than

object(for example, French lui as seen above which would be agoalanaphor). ↩ -

There is, however, a question of whether weak pronoun replacement should be obligatory or not: that is, if we see a regular anaphor right now such as “this,” we make two copies of the parse: one with the replacement, one without. In the case where we detect an anaphor, should the replacement be obligatory? I believe it should be, though, as with many other Parser 2 features, I believe we can continue to parse other options with no replacement but let the scoring system kill those parses off. If a verb has a clitic attached to it but we do not remove it, it most likely will do very poorly in scoring anyway. ↩